From the author of The Stream With No Name, Part 1

Please contact This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. if you have any questions or further info to add.

The Knabb Stream and Valley: Part 2

February 2021

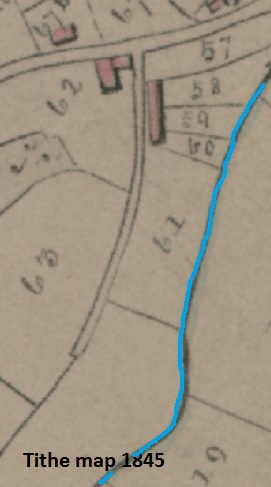

In Part 1 the road shown on the 1845 tithe map was considered as significant. For many years it was an alternative to continuing alongside the stream, due to its the depth and speed of flow. A ‘causey’, consisting of slabs, may well have enabled people and horses to cross marshy ground and, although this may seem an arduous way into Kingsley, it was historically embedded in the ways of people at the time.

In Part 1 the road shown on the 1845 tithe map was considered as significant. For many years it was an alternative to continuing alongside the stream, due to its the depth and speed of flow. A ‘causey’, consisting of slabs, may well have enabled people and horses to cross marshy ground and, although this may seem an arduous way into Kingsley, it was historically embedded in the ways of people at the time.

Roads were often no more than rutted, potholed tracks as, often, even Roman roads were left unused by the Saxons, many of whom preferred their old trackways. Nothing much changed until the medieval period when it was left to each parish to maintain their own roads. However, improvements were few and far between with roads often remaining in a dire state. As the 1855 Highways Act proclaimed, ‘for amending highways, now both very noisome and tedious to travel on, and dangerous to all passengers and carriages.’ Unsurprisingly, the great majority of people walked except for those who had the benefit of horses. Travelling was via ancient long-distance trackways, many dating to pre-historic times, as well as a network of local tracks. The result of this is that many of the footpaths we use today were established a long time ago.

I believe the Knabb valley was such a well-used route at least until the early 18th century. Indeed, it was possibly used in pre-history and almost certainly in medieval times when trade was flourishing. This was a time when all the goods required to maintain towns and villages had to be brought in, if not by carts then likely carried on packhorses. For centuries these tough, sturdy animals were the backbone of Britain’s economy, moving goods such as coal, cloth, timber, foodstuffs and many other items as part of packhorse trains, many of which could be 30 horses long. In this manner goods were moved across the country and in places like the upland areas of the Pennines etc, hundreds of journeys were made every week.

An example, from the 11th century, is the Cheshire salt trade, that relied mostly on packhorses, though also with some oxen and carts, to send salt all over the country. Such journeys are a history in themselves and such a fascinating one. Sadly, tracing these routes in Cheshire is especially hard as they were such a feature of life as not to be recorded. The low-lying landscape offered so many packhorse routes as to make any idea of their origin or destination hard to define. One passed through Kelsall into the forest and, possibly, along the Knabb and onwards to Frodsham, or using the crossing points of the river Weaver to Manchester or even into Derbyshire.

Packhorse bridge Calva in Cumbria

Packhorse bridge Calva in Cumbria

Seemingly, I have strayed from the ‘lost’ lane in the opening paragraph. Yet, the journey has come full circle for a purpose. Be it fact or fiction it does offer a hypothesis, albeit one that is open to challenge, for the existence of that lane.

Unlike a brook, the Knabb once showed features of a ‘mature’ river; mainly it’s meandering course. As such it would have been wider, deeper and not controlled within artificial banks like today where only one-third of its length is natural before it becomes culverted under Brookside, remerging again at the junction of The Hurst where it meets Brookside again before flowing on to Mill Lane and beyond.

It is a confused watercourse. After leaving a lake at Crofton Lodge, it flows, brook-like, without obvious banks into the Knabb to then appear like a mill stream in its controlled straightness and speed. It then falls some 5m (a waterfall once?) and continuess as natural, though not as it entered.

Digressing again, I suggest the lost lane allowed travellers on foot and on horse to bypass the stream (where the steps are today.) Even a hardy packhorse with its 90kg load, might stall in such conditions given the daily mileage they endured.